Besides equalization, compression is easily the most-often used effect while mixing. While properly deployed compression will really make your mixes pop, you can also do a lot of damage with the effect.

In this post, we'll explore common compression mistakes and how you can avoid them.

#1 — Not Getting it Right at the Source

When you compress a bad-sounding track, it accentuates its worst qualities. Subpar room acoustics will be made painfully obvious, background noises will be brought to the forefront, and unwanted squeaks, creaks, and buzzes will abound.

So, before you compress your track, solo it and give it a thorough audition. If it was recorded poorly, no amount of compression or processing is going to give it a pro-level sound.

Your best option is to re-record the offending track. If this isn't possible (for example, you're mixing somebody else's project), you may want to investigate other options.

When dealing with a drum track, sample replacement is an excellent option. If you have access to a DI'd guitar or bass track, try cleaning up the track as best you can, then use amp simulation software to take it the rest of the way.

As for keyboard parts, there are loads of excellent audio-to-MIDI applications out there that would allow you to replace the parts with virtual instruments.

Once you achieve a solid sound, you'll be able to apply compression without making the track sound worse.

#2 — Compressing a Muddy Track

Other things to be aware of before you deploy a compressor are low-frequency mud and unwanted resonances. Both issues — even if they're largely inaudible — can cause unpredictable compressor behavior.

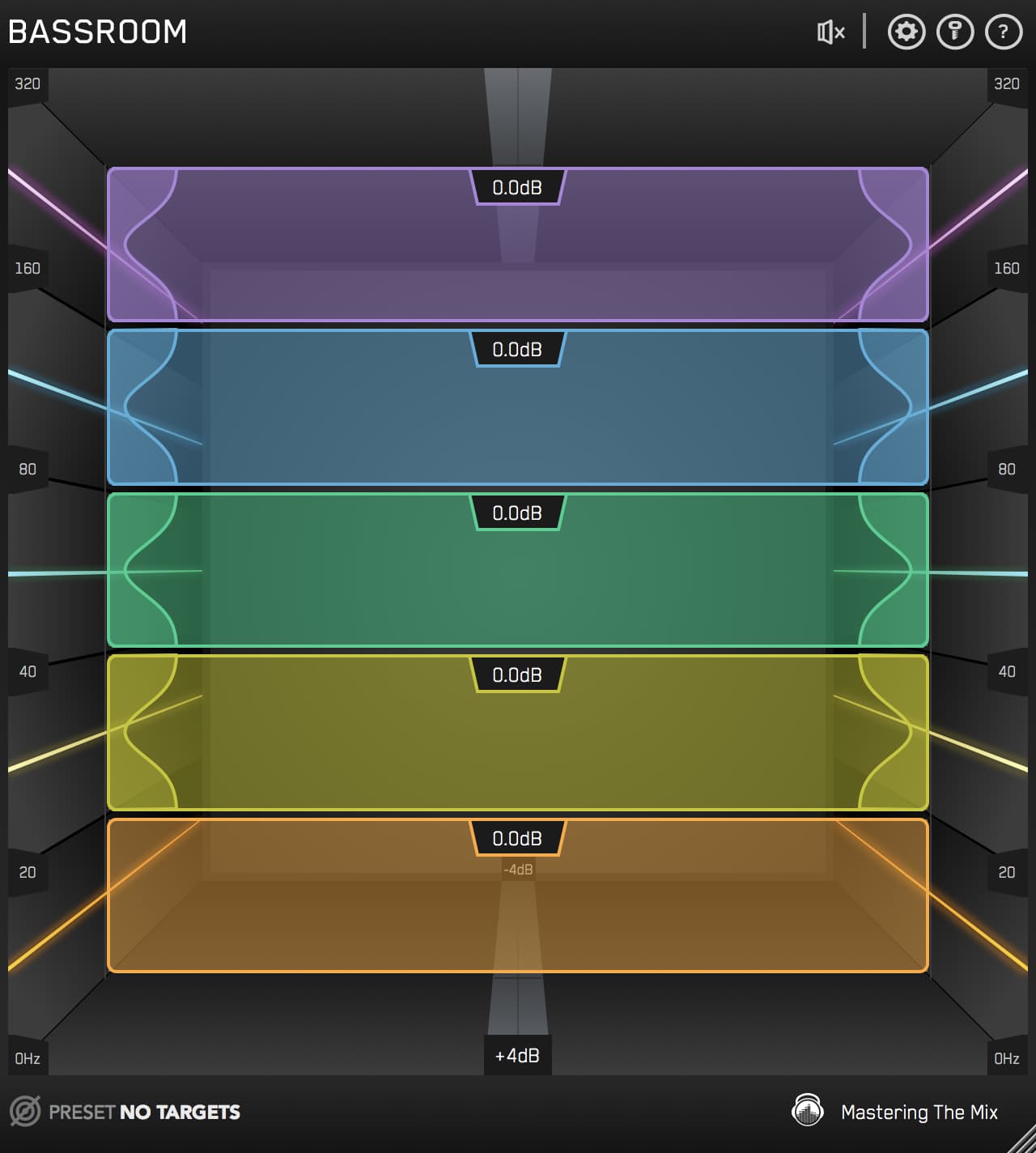

Your main line of defense against unwanted low end is a highpass filter. This type of filter is a standard feature on most parametric EQ plug-ins — including the stock one that come with most DAW software.

For bass-heavy instruments, you'll want to start with your EQ's minimum cutoff frequency and a gentle 6–12dB slope. Increase the cutoff frequency until the track starts sounding thin, then decrease the frequency until you get the sound you're aiming for.

For instruments without a lot of low-frequency content, start with a cutoff frequency around 30Hz and follow the same steps as above.

Resonances are, in a nutshell, a buildup of frequencies within your mix. Not only do these frequencies rob your tracks of dynamics and headroom, but they can also make your compressor do all kinds of wacky things.

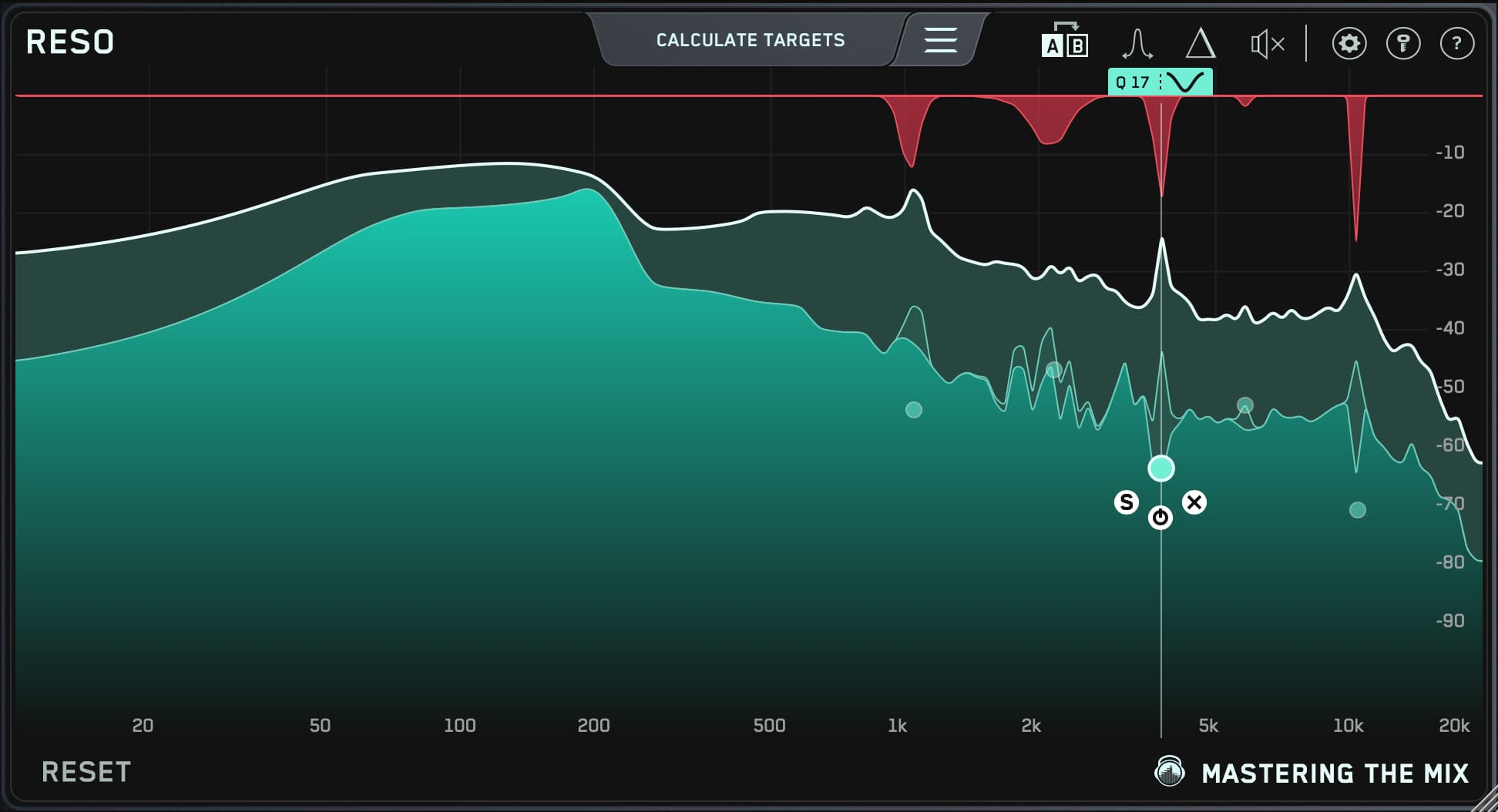

Our RESO plug-in is an easy-to-use solution for getting rid of unwanted resonances — automatically.

Simply place it on a track, then click the Calculate Targets button. RESO will then create Target Node and provide you with helpful setting suggestions for achieving a resonance-free track.

#3 — Compressing Too Many Frequencies

If your compressor responds erratically, it may be reacting to the wrong frequency element. This is especially obvious when placing a compressor on a busy track, such as a full-frequency synth sequence, or a stereo bus.

That's where sidechain EQ'ing comes in. Using a sidechain EQ will make your compressor more or less sensitive to certain frequencies or ranges of frequencies depending on if you boost or cut those frequencies, respectively.

To deploy this technique, simply split your track or stereo mix so it's feeding your main output along with an equalizer that's connected to your compressor's sidechain input. Then use the EQ to filter out any problematic frequencies.

A common use for sidechain EQ is to prevent your kick and bass from triggering your mix bus compressor. By cutting selective low frequencies or creating a 150–200Hz highpass filter on your sidechain EQ, you'll be able to keep your compressor from freaking out whenever your kick or bass sound.

A properly dialed-in sidechain will enable you to add more compression to your track or bus without the problematic behavior. Before you start routing signals around; however, check your compressor — many compressors include a built-in sidechain EQ function.

#4 — Not Applying Automation Before Compression

While compressors are designed to rein in overly dynamic sources, they're not intended to take the place of your faders. Abusing compressors in this way will give your tracks an artificial, lifeless quality that's guaranteed to lower the quality of your mix.

Since most DAWs include built-in automation, fixing runaway dynamics with your faders is a piece of cake. Start with 1–2dB boosts and cuts. If your track gets too quiet, boost; if the track gets too loud, cut.

This is just a starting point, of course. You'll be tweaking your automation parameters all throughout the mixing process.

Aim to get your tracks 90% of the way there with automation. Then you'll be able to apply compression in a more natural way.

Overcompression should be a stylistic choice, not a corrective measure.

#5 — Using Improper Attack and Release Settings

Your compressor's attack and release settings are among its most important. Of all the parameters on a compressor, attack and release have the most significant effect on its behavior.

For example, if your track sounds muffled or distant after applying compression, try dialing in a slower attack. Most likely, your compressor is swallowing your track's transients.

You'll want to set the compressor so the transient pokes through before the gain reduction kicks in. This is the secret to intelligible vocals and punchy drums.

Pumping and breathing — obvious audible compression with a rhythmic, ducking component — is another unwanted side effect of improper attack and release settings.

If you're struggling with this, adjust your compressor with a medium attack time (around 15ms). Then dial in a medium release time (around 40ms).

After that, keep tweaking the release setting until the pumping becomes inaudible or pumps in a way that sounds musical to you.

It's also possible that you have the compressor's gain reduction set too high. That said, a mere 3dB of compression can cause audible pumping and breathing if your attack and release settings are off.

#6 — Smashing Your Track Too Hard

If your track sounds washed out or distorted after applying compression, you likely have the compressor's ratio set too high.

Simply put, a compressor's ratio sets the amount of gain reduction. The higher the ratio, the more extreme the compression.

So, what do these ratios sound like? Here are a few common settings:

- 1:1 is no compression

- 2:1 is light compression (a great choice for mix bus duties)

- 3:1 is moderate compression

- 4:1 is substantial compression (a great starting point for obviously compressed tracks)

- 8:1 is very noticeable compression

- 10:1 and greater will sound rather slammed unless used in tandem with a very light threshold

- ∞:1 is limiting, and nothing goes over the set volume

We all love the sound of compression but slamming everything is your one-way ticket to a lifeless mix with zero dynamics — use responsibly!

#7 — Using the Wrong Type of Compressor

Compressors aren't one-size-fits-all devices. Different compressors deliver a different sound — especially if you're using a hardware compressor or an analog-modeled plug-in.

If you're aiming for a transparent sound, deploying a "character" compressor, such as a Urei 1176 or an Empirical Labs Distressor, won't give you the sound you're searching for.

Conversely, a "transparent" compressor, such as a dbx 160 or the generic stock plug-in in most DAWs, won't infuse your tracks with vibe and mojo.

You can also get the best of both worlds by using two compressors together, a transparent one to catch stray peaks and a second character one to add vibe and fullness.

Set the first compressor with a high compression ratio (around 12:1) and a fast attack and release. Most importantly, set the compressor so that it isn't exceeding 2dB–3dB of gain reduction during the loudest peaks.

After that, set the second compressor with a slow attack and a release until it blends well with your mix. Use a substantial compression ratio (between 4:1 and 8:1), then tweak the threshold unit you like the sound you're getting

Don't be afraid of using aggressive settings on the second compressor. Since the first comp is taming the large peaks, the second unit won't be as likely to overcompress your track.

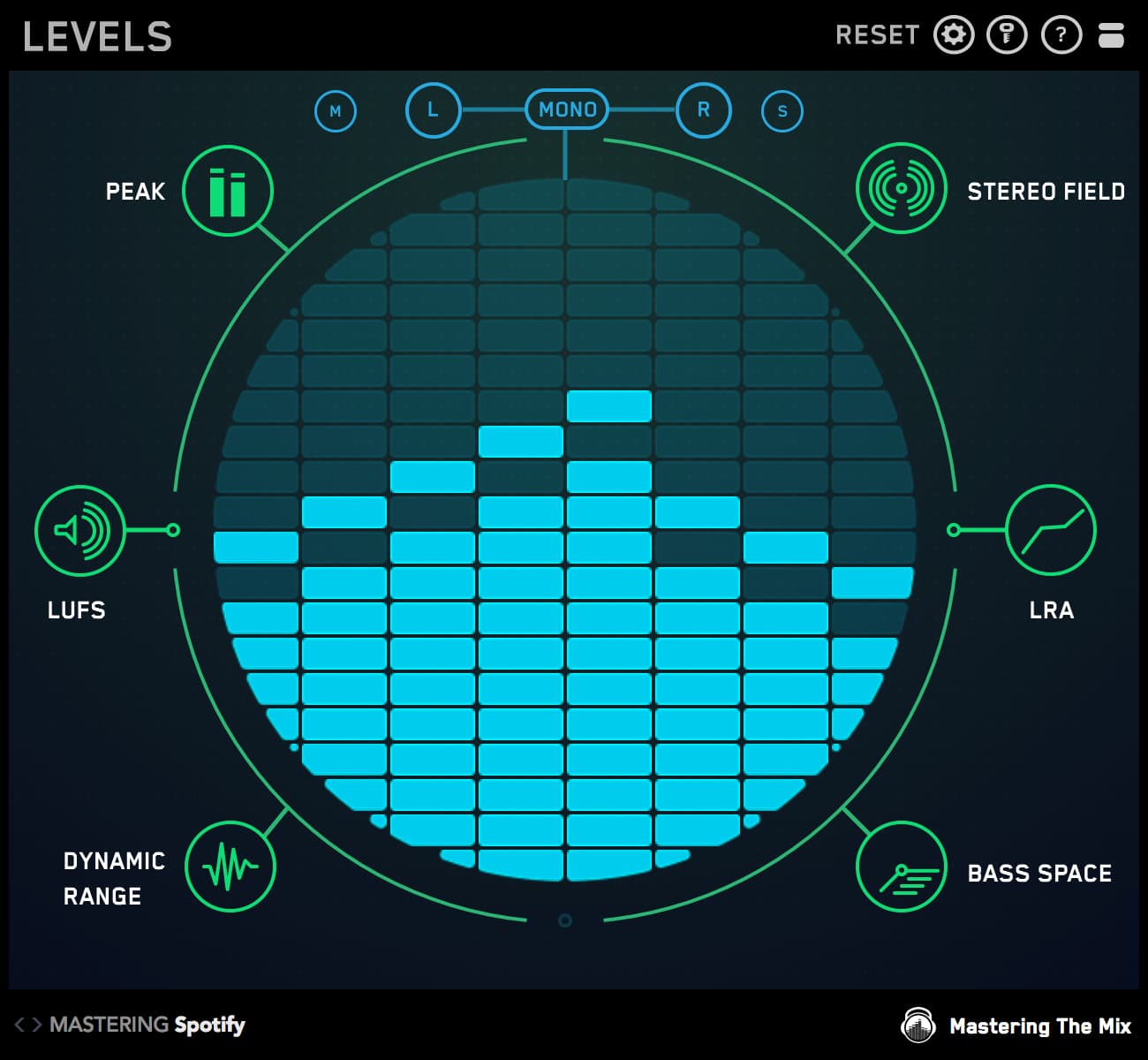

Bonus Tip — Use a Reference Track

It's easy to lose your sonic perspective after you've listened to the sound of your own mix for hours upon hours. That's where reference tracks come in.

A reference track is a professionally mixed and mastered song that you use for a reality check. This will help you regain your perspective, and it will ensure that your song sounds as great as — or better — than the next song on your listener's playlist.

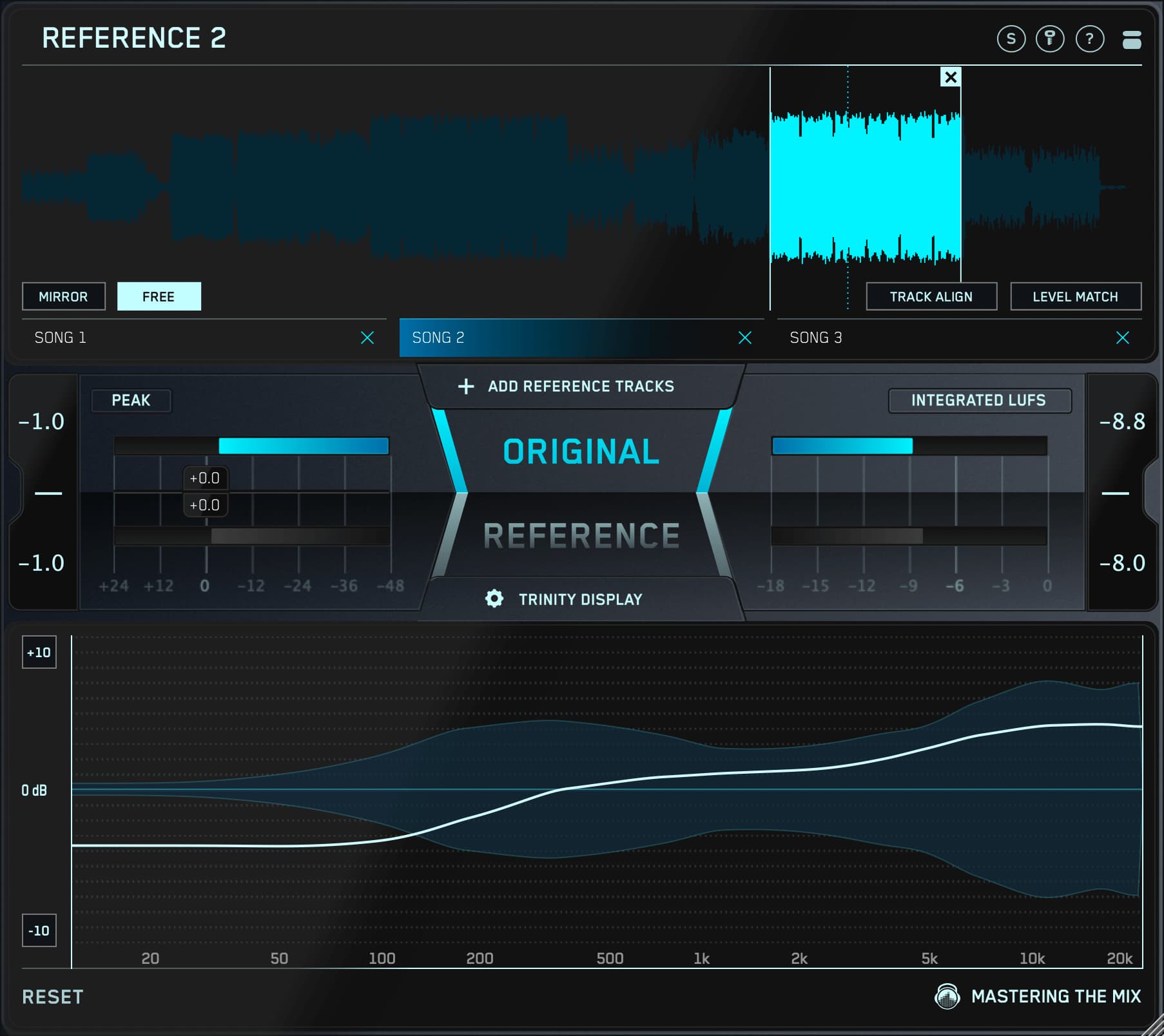

Cueing up a suitable reference track is a breeze with our REFERENCE plug-in. Simply import a reference track you'd like to emulate, preferably within the same genre you're working on.

Next, listen closely to the reference track and use it as a guide for how yours should sound. This will help you with levels and automation, plus it will aid you greatly in nailing the right sound and behavior for your compressors.

Conclusion

Mastering the art of compression is a necessity if you want to master the mix. And the best way to improve is to keep mixing!

While you're learning the ropes, keep following our blog. It's chock-full of useful tips and tricks we've gained from hard-earned experience.

We’ll help you skip the tedious trial and error and do things the correct way right from the start!