If you spend any amount of time on internet forums searching for mixing tips, you'll run across lots of conflicting information. While there's tons of great information out there, there's also a great deal of misinformation.

In this blog post, we're going to debunk eight common mixing myths. We'll also provide you with factual information you can use to elevate the quality of your mixes.

Myth #1 — Celebrity Plug-in Presets Will Give You a "Pro" Mix

Many EQ plug-ins include celebrity presets programmed by Grammy-winning engineers.

This looks great from a marketing standpoint. That said, there are no top-secret, one-size-fits-all EQ settings — EQ doesn't exist in a vacuum — so these presets will likely be of little use on your own mixes.

Every track is different. Just because an EQ curve works in one instance — even if it's on a legendary hit song — that doesn't mean it will produce similar results in another situation.

It doesn't matter how many hits a world-famous engineer has under their belt; they have never heard your mix. Therefore, their EQ settings won't be of more use to you than any other generic run-of-the-mill preset.

After all, if crafting the perfect track were as easy as clicking on a preset, all mixes would sound like the Billboard Top 100, and the big-name mix engineers would be out of work.

There's only one tool you need to determine the best plug-in settings for your track: your ears!

If you feel like your ears need a helping hand, our MIXROOM plug-in offers an efficient — and effective — method for dialing in EQ settings. MIXROOM has presets that actually work, as they’re set specifically based on the tonal balance of the material you’re EQing. MIXROOM is an intuitive EQ that gives you application-specific presets and target frequencies based on a reference track.

It's a cinch to use — simply instantiate it on your track, choose an appropriate channel preset, or create a custom target value with the Target icon on the bottom left corner of the plug-in's interface, and import a reference track.

MIXROOM's Target EQ Curve serves up a professional sound on a silver platter — without the mind-numbing trial and error. Beyond that, you can use the Add Smart Bands button to call up EQ bands that match the Target EQ Curve.

MIXROOM is, by far, the easiest way to obtain an intelligent starting point for EQ-ing your tracks.

Myth #2 — You Should Automatically Highpass Every Track in Your Mix

While almost every mix tutorial stresses the effectiveness of highpass filtering for eliminating unwanted low-frequency mud (and rightly so), its overzealous use is a one-way ticket to a thin-sounding mix.

It is likely that you'll need to instantiate a highpass filter on most of the tracks in your mix; however, you shouldn't do so in a willy-nilly fashion. And you definitely don't want to slap a filter on everything, set them all to 100Hz, and call it a day.

Use your ears instead (are you noticing a pattern here?). Listen to your mix — with all the tracks engaged — and make decisions on a track-by-track, case-by-case basis.

On bass-heavy instruments like kick drum and bass, begin with your EQ's minimum cutoff frequency and a gentle 6–12dB slope. Increase the cutoff frequency — with your entire mix playing — until the track begins to sound thin, then decrease the frequency until you get a sound you like.

For instruments without a lot of low-frequency content, begin with a cutoff frequency around 30Hz and follow the same steps as above.

Can't make the filter sound right? If so, try removing it altogether. Maybe you don't actually need it!

At the end of the day, you want to adjust your filters for transparent results. Once a track starts to lose body, you've gone too far.

And a mix built from thin-sounding tracks is guaranteed to sound tinny, thin, and possibly even fatiguing.

Myth #3 — EQ Always Goes Before Compression

For some reason, mix tutorials will often stress — or even mandate — that you always place an EQ before a compressor in a signal chain. And they'll make this statement without even listening to your mix!

When you place an EQ before a compressor, it allows you to tailor how the compressor reacts to your source. For example, if the excessive low-frequency content of a kick drum is causing your compressor to pump and breathe, you can use the EQ to dial down the offending frequencies until the compressor behaves itself.

There's a tradeoff to this approach, however. If you try to boost a frequency with an EQ then feed it into a compressor, the compressor will essentially "undo" the boost with gain reduction.

In these situations, you'll want to place the EQ after the compressor. Placing an EQ after a compressor is also a great way to compensate for the high-frequency dulling that often results from heavy compression.

That being said, placing an EQ after a compressor will "undo" some of the compressor's dynamic range adjustments. So, if you're trying to use a compressor or limiter to contain errant peaks, running a compressor into an EQ is generally not the way to go.

The moral of the story is this: place your effects in whatever order sounds best for your specific application (translation: use your ears).

Myth #4 — You Should Always Cut (and Never Boost) with an EQ

You've probably heard well-intentioned folks advise you to never use EQ boosts, and that you should always use EQ cuts.

While we agree that cutting frequencies is more often than not the preferred way to go, you should take any advice that includes the words always and never with a grain of salt — there are very few absolutes in mixing.

This whole never-use-boosts idea likely stems from the fact that you can do more damage with an EQ by boosting frequencies than you can by cutting them. Few things will create a boomy, harsh mix faster than overenthusiastic EQ boosts.

Equalizers work in both directions. That said, no matter how you're using an equalizer, the trick to effective EQ-ing is to use it gently.

Thus, if your track needs a subtle high-frequency lift, boost it. However, if your track fails to cut through your mix — even after a hefty EQ boost, try cutting competing frequencies in other tracks that are masking the track you're trying to boost.

And if you're wading through low-frequency mud, try freeing up space by cutting the sub-100Hz frequencies on tracks without essential low-frequency information.

And we'll say this again: a little EQ goes a long way.

Unless you're aiming for an obvious "effected" sound (such as a telephone-like effect), avoid being ham-fisted with your equalizer's gain controls.

A slight 5–10kHz bump may be all that's needed to add sparkle to an acoustic guitar, piano, or synth track. You can also apply a tiny boost in the 500–600Hz region to add body or cut a bit around 250Hz to lend more clarity to your track.

Myth #5 — Acoustic Treatment Isn't Necessary If You EQ Your Room

Mixing in an untreated space can make life difficult. That's why any credible studio tutorial will recommend that you add acoustic treatment to your mix room.

This is because untreated rooms suffer from a huge number of common sonic deficits, such as flutter echo, standing waves, boundary proximity issues, and more.

Many engineers working in untreated spaces rely on room-correction software to level up their room acoustics instead of investing in acoustic treatment.

At its most basic, this software takes an acoustic snapshot of your room then creates an EQ curve to compensate for its sonic deficiencies. While this type of solution is better than nothing, it doesn't actually fix your room; rather, it changes the way you perceive the room.

To put it bluntly, a heavily EQ'd room with horrible acoustics is still a room with horrible acoustics. While EQ can fix some acoustic issues, it can't eliminate slapback, flutter echo, and inconsistent acoustic anomalies as you move about the room.

That's why you need proper acoustic treatment, such as absorption and diffusion panels, bass traps, and monitor decouplers. When they're placed and used appropriately, these items are the best way to improve your room's sound.

As far as room-correction software goes, it's a great solution to use in tandem with — rather than in lieu of — acoustic treatment. After all, the only way to achieve perfect acoustics is with a purpose-built space designed by an expert acoustician.

If you're wanting to transform a common residential bedroom into a usable mix space, using both acoustic treatment and room-correction software is a great way to bring it even closer to pro-studio specs.

Additionally, listen with high-quality studio monitors and position them properly, in the shape of an equilateral triangle, with their tweeters at ear level.

Lastly, monitor at a consistent — and safe — volume. The optimal level for most small home studios is around 73–76dB SPL (C weighted).

Myth #6 — Boosting "Air" Frequencies is a Waste Because People Can't Hear Past 20kHz

Many engineers add "air" to a dull track by boosting ultra-high frequencies above 20kHz. This works particularly well on vocal tracks and during mastering.

But wait… Isn't the upper threshold of human hearing 20kHz? Under the best of conditions?

Yes, this is true. But don't let anyone tell you that boosting ultra-high frequencies, say 25kHz and above, doesn't do anything, because it does.

This is because most EQ filters, depending on their curve and Q setting, affect more than their center frequency. Thus, a 25kHz filter can easily affect audible frequencies below 20kHz.

This is especially true of the filters on analog equalizers (and plug-in emulations of analog equalizers), which oftentimes lend a subjectively pleasing quality to everything you run through them. That's why many top-of-the-line mastering EQs have high-shelf filters that extend upwards of 30kHz!

Myth #7 — Compressors Are the Only Way to Fix Overly Dynamic Tracks

Back in the day, prior to the advent of automation, it would take an entire handful of engineers to mix an album. They would all take their place at the console, put their finger on their assigned faders, and move them at just the right time.

Today, every DAW includes built-in automation. Yet, even with this miraculous technology at their disposal, many contemporary engineers believe that the only way to fix a track's dynamics is with (over-)compression — they never even touch a fader!

This, unfortunately, is why many modern productions sound lifeless, artificial, and completely devoid of dynamics. A well-crafted mix is a living, breathing organism; something you can't achieve if you smash everything with a compressor or a limiter.

So, instead of reaching for a compressor plug-in first, try using your DAW's automation to even out your tracks' dynamics.

For starters, use 1–2dB boosts and cuts. If your track gets too quiet, boost; if your track gets too loud, cut.

This is just a starting point, of course. More than likely, you'll need to adjust your automation parameters all throughout the mixing process.

Try to get your tracks most of the way there using automation. Once you become adept at this process, you'll be able to make any track sit intelligibly within a mix without even touching a compressor.

We're not saying compression is bad, of course — it's still one of the most important mixing tools in your arsenal. We're simply suggesting that you wait to deploy dynamic compression until after you nail your levels with automation.

Then, after you've programmed your automation, throw on a compressor (or more than one compressor) to sort out any remaining dynamics issues, to add coloration, or both.

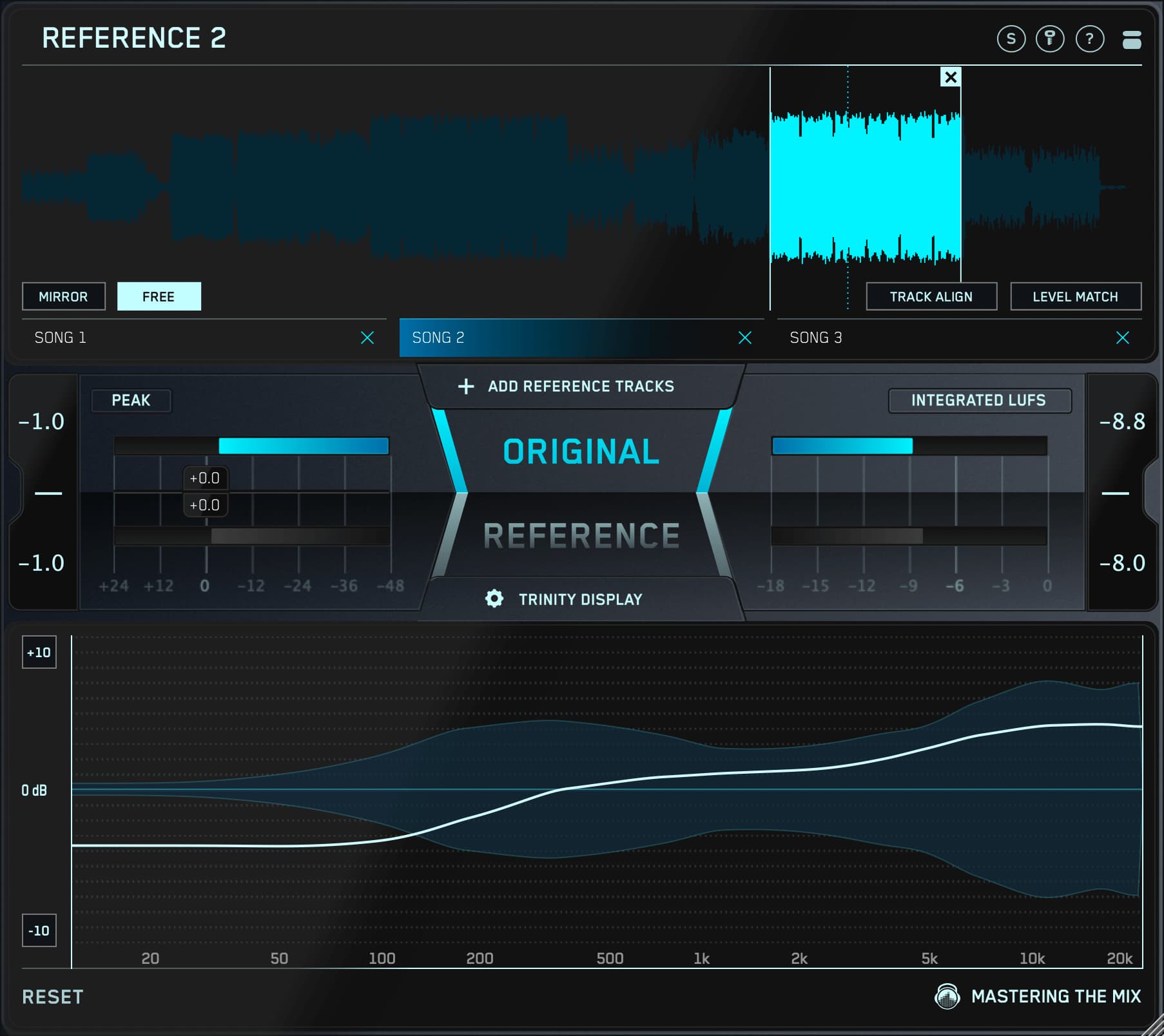

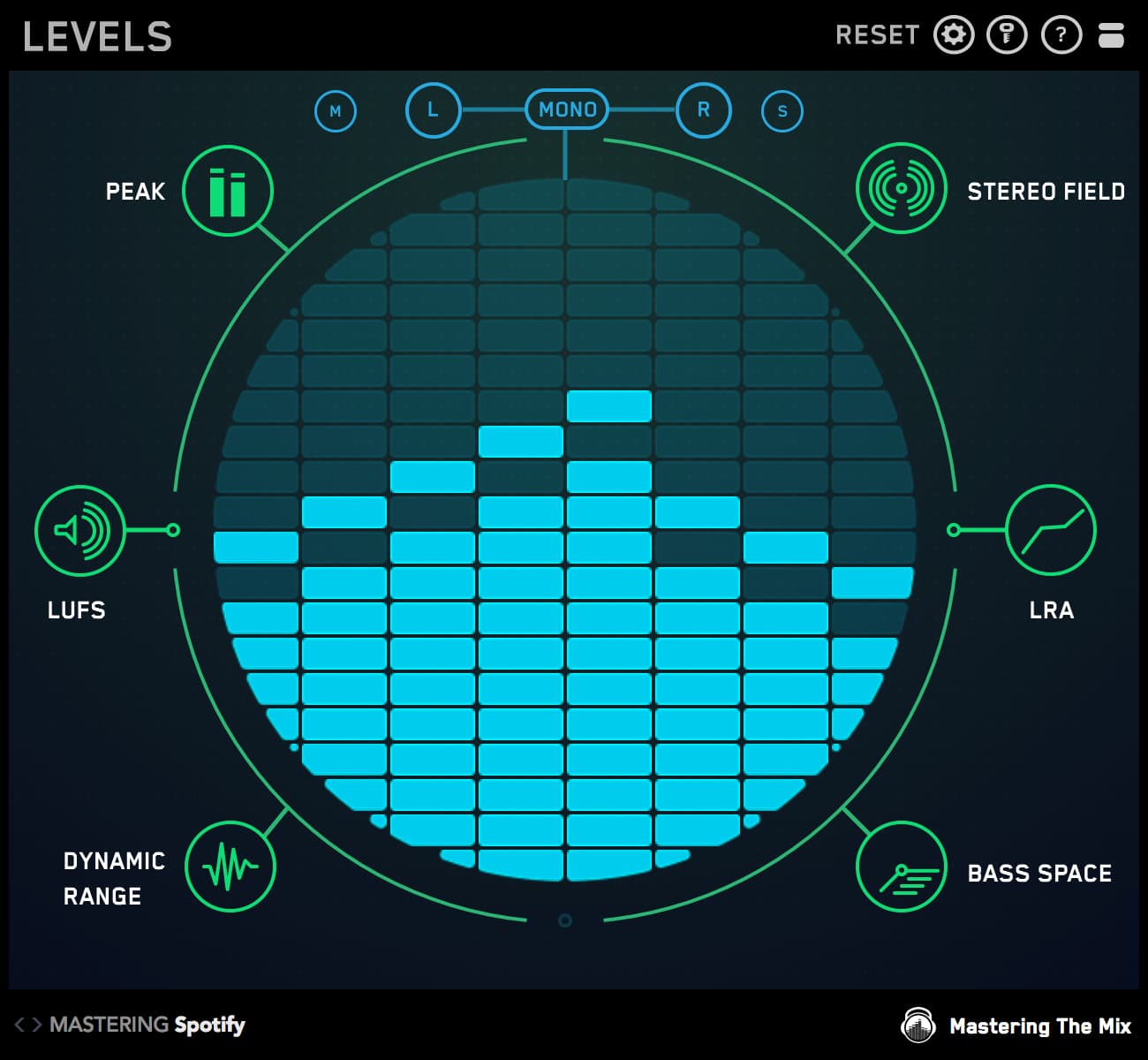

If you're having trouble determining if your mix is dynamic enough, our LEVELS plug-in offers an incredibly effective way to identify issues with dynamic range, as well as loudness, peaks, stereo spread, and more.

Myth #8 — Analog Gear is Superior to Plug-ins

There's a common misconception (especially on internet forums) that analog gear is always superior to plug-ins, in every situation and in every application. When digital was in its infancy, this was probably true; however, digital processing has come a long way since 16-bit audio engines and Motorola 68000 chips.

The truth is, there are benefits — and drawbacks — to both types of technology.

Analog hardware contains tubes, transistors, photocells, capacitors, and transformers; plug-ins don't. That's what gives classic analog gear its magical sound.

That said, digital plug-ins can achieve feats that vintage analog gear can't come close to. Even analog-modeled plug-ins oftentimes include features that their analog counterparts lacked, offering you a similar sound with expanded functionality.

Unfortunately, plug-ins are bound to your computer, so if you update your OS or DAW, your plug-ins can stop working. Like all things related to computers, plug-ins suffer from built-in obsolescence if you want to keep your computer and DAW up to date.

Conversely, analog gear doesn't care what kind of computer you use (or if you use a computer at all), and it will continue to operate the same way in 20 years as it does today. That said, transistors blow, resistors fry, and capacitors dry out — you'll eventually need to have your analog gear serviced, and vintage-spec'd replacement parts can be hard to come by.

Plug-ins are generally much less expensive than analog hardware. Plus, you can instantiate as many across your project as your computer can handle. Recalling a digital project is also considerably faster than having to reset all of your analogue gear to the correct settings.

To top it off, modern analog-modeled plug-ins are getting so good that even golden-eared analog die-hards have trouble identifying them in a double-blind listening test.

But are plug-ins good enough for pro-level engineers? According to Grammy-winning mixers Andrew Scheps, Tchad Blake, Michael Brauer, Dave Pensado, Phil Tan, and many others, the answer is "yes."

Our advice? Use the gear that inspires you, facilitates an intelligent workflow, and — most importantly — gets the job done.

Conclusion

It doesn't matter how many times you repeat misinformation, that doesn't make it true. But that's why this blog exists: to provide you with accurate information, along with tips and strategies that will help you improve your craft.

Keep following for more!