If width is the holy grail of mixing, depth and height are equally sanctified. These dimensions sell a mix as something worth more than a listen—something to inhabit, something to appreciate over a lifetime.

Naysayers will tell you one cannot achieve depth in the digital domain; an expensive analog path is required, they’ll say.

But this is not the case: while high-end gear can add to the soundstage by virtue of its mere existence, gear can’t fix poor technique.

Here is the good news: techniques for achieving dimensionality are simple to explain. Now, here’s the bad: they’re not easy to master, and they take time to digest.

Without further preamble, let’s dive into some basic principles for preserving depth and creating height in your mix.

-

EQ and level relationships create depth

Let’s start with a single sound: a vocal.

Left on its own, this vocal doesn’t appear as though it’s coming from anywhere. But two simple tools can help us sink the vocal into the soundstage: a fader, and an equalizer.

As a sound moves farther away from you, it seems lower in level. It also exhibits less high-end.

Depending on the location you’re trying to evoke, the low end may also be curtailed (the exception: if you’re trying to recreate the great outdoors, a sound may exhibit additional low end; keep this in mind).

If we lower the fader and add the kind of EQ displayed below, we can push this vocal into the soundstage.

Seems farther away, right?

But here’s the thing: I’ve tricked you. This vocal would not sound farther away if I never showed you the unprocessed version.

We need to establish a relationship between two elements to create depth.

This relationship shows up in a variety of ways. It can comprise two different instruments, and it can also involve an instrument and its corresponding delay or reverb.

Even a single instrument, recorded with one microphone, can exhibit a sense of depth, provided the room has a certain character to it, and provided you’ve captured the room with your microphone.

Let’s show off how relationships create depth by pitting other elements against this vocal. We’ll bring up four instruments: a bass, an acoustic guitar, and two electrics.

This is an unexciting, listless balance of the instruments. Using only faders and EQs, we can achieve a modicum of depth.

Now we have a soundstage—and it was easy!

It becomes harder, however, if you consider all the elements of the modern mix. When you’ve got 100 tracks in a session, you have to rely on other tools, as EQ will become necessary for other operations besides establishing depth.

You, my friend, need further ways of fostering dimensionality.

-

Create depth through a reverb’s early reflections

Most reverbs give you control over early reflections and late reflections (also called the tail).

Most reverbs give you control over early reflections and late reflections (also called the tail).

To conceptualize early reflections, let’s imagine a room. Early reflections are the first points of reflection off this room’s walls—the first hit of a reverberation.

These reflections have a huge influence on how an instrument is perceived. Observe this example of an unprocessed drum kit.

If I wanted to impart some depth, I could do so with a reverb’s early reflections. I’d time the early reflections appropriately, turn the late reflections all the way off, and blend back to a reasonable degree.

With a Nimbus verb from Exponential Audio, it could look like this:

And sound like this:

The difference is subtle, but it’s there. Let’s isolate the early reflections and describe what they’re doing for us.

On their own, we hear a dark, out-of-phase drum kit. But blended in with the original sound, we notice that these early reflections contextualize the kit within a space.

-

Create Depth through a reverb’s late reflections

Now, what happens if we add late reflections to the signal? What do they do to our sound?

If early reflections give us an immediate sense of an instrument’s location, the tail tells us what kind of location we’re dealing with. They help us distinguish a church from a chamber, a bathroom from a river basin.

Let’s return to our drum kit. We’ve given it some depth with some early reflections, and now we’ll take it to church by adding in the tail.

Note the long reverb time, the largeness of the space, and low-mid balance tilted to favor the low-end. These facets help us distinguish the specific location, which you can hear in the below example, exaggerated more than I would in an actual mix:

To round out what reverb can do for us, let’s return to our band from the first tip—let’s see what our singer, her bassist, and her backing guitar players are up to.

Didn’t it seem as though the singer was also playing guitar? Both sounds felt like they were coming from the same location.

When we tailor our early and late reflections correctly, we can paint a different picture: we can make it feel as though each instrumentalist is a different person.

-

Time your delays for depth

Here’s a general rule of thumb: A delay in sync with a song’s tempo helps push an element back into the soundstage. A delay completely out of sync with the tempo does the opposite—it brings the element closer to us.

Here’s our drum kit again.

Let’s add some delay to the overheads. This stereo delay will match the tempo of the song and will be brought in on an auxiliary return at about -28 dB.

The delay is barely perceptible—but I invite you to compare this example to the unaffected drums. Listen to the space around the ride and the hi-hat specifically; you’ll note something missing as you do your comparisons, a 3D quality that simply leaves us.

Now, let’s build on this kit. Let’s see what happens if I add an echo to the snare, but time this echo to stand out from the track.

The echo is Logic’s Tape Delay, measuring 61 ms.

The delay is mixed quite low—17.8 dB on its own aux. Yet the snare pops out so much more. It’s not an EQ thing, nor is it compression: this is the power of delay.

When we blend our reverbs and our delays together, the difference is more stark:

These effects are cumulative: combining more than one of them will change the depth of field exponentially.

-

Create depth by avoiding over-compression

Over-compression ruins depth. Why?

A compressor restricts dynamic range. The amount of space between the loudest transient and softest signal is constrained by the compressor.

The loudest sound is pushed lower in level—or is it? The makeup knob says otherwise.

Turn up a compressed signal, and all the little goodies sunk deep into the mix are now louder than before. You have effectively kneecapped your depth of field.

But hang on, don’t some people claim compressors add depth—particularly vintage, vibey ones? Yes they do, and here’s why:

Use a compressor to the best of your ability, and all the deficits become superpowers: manipulating the space between the loudest transient and the quietest signal can actually improve your soundstage if you master your attack and release controls.

Deploy these parameters correctly, and you can emphasize the transient while keeping all the background goodies low in level. You can, for example, emphasize the hard strike of a snare without bringing up the ghost notes.

Take a finished, uncompressed mix and add a compressor. Keep the attack slow and the release relatively quick. Compare these settings to their opposite: a fast attack and a slow release. You’ll begin to hear what I’m talking about—especially if you’re keeping an ear out for it.

-

Create depth by transient shaping

Transient shaping can pull sounds closer to you, or push them farther away. Observe the relationship between three guitars.

Let’s run the guitar on the left through a multiband transient shaper, one that emphasizes the pick attack and the low-mid chunk of the left-most rhythm guitar.

Now, hear how we sink the guitar into the background by lowering the attack and emphasizing the sustain.

Quite a difference. This is exactly the point: you must pay attention to transients when establishing depth—and you must shape them to your advantage.

-

Create height with EQ relationships

Height is a psycho-acoustic illusion based on EQ trickery. It depends on relationships: a sound all by its lonesome cannot feel tall, not unless it’s contrasted with another sound.

A bass-heavy sound will feel closer to the ground than a brighter one. A trebly sound, devoid of lows, can appear to float higher than a bass.

But I can’t demonstrate any of this without an example full of relationships.

Here’s a vocal and a bass with no processing:

If we cut some highs out of the bass, and affect the vocals like so:

We can alter the perceived height of the mix:

Here’s an interesting ripple on this particular relationship: it’s not just frequency discrepancies that give us the illusion of height. Time plays a factor as well.

If a sound has been established for a long period of time and loses its low end suddenly, it can appear taller, even if no other sound exists. Post engineers take note: this can be especially effective in film, podcasting, and other audio media.

It also leads us to our final tip.

-

It’s all about contrasts

A mix with stagnant panning positions, static levels, and uniform equalization will begin to appear as one monolithic block of sound, no matter how wide, tall, or deep it feels at first. Make sure to use contrasts to your advantage.

Give us a vocal that’s full range at the outset, and then take out some lows for the chorus if you want to lift it in height. Automate the early reflections to push an element farther back into the mix over time.

Any of the parameters we’ve talked about so far can be automated—and they’ll all create dimensionality for the listener.

A static mix is the enemy of depth, so use tricks of automation to your benefit. Do so for an element, for a verse, or for both—just remember to pay attention to the relationship between instruments while you go about your business.

Conclusion

Again, there are no exciting secrets here. It’s a balancing act, much like achieving good stereo separation.

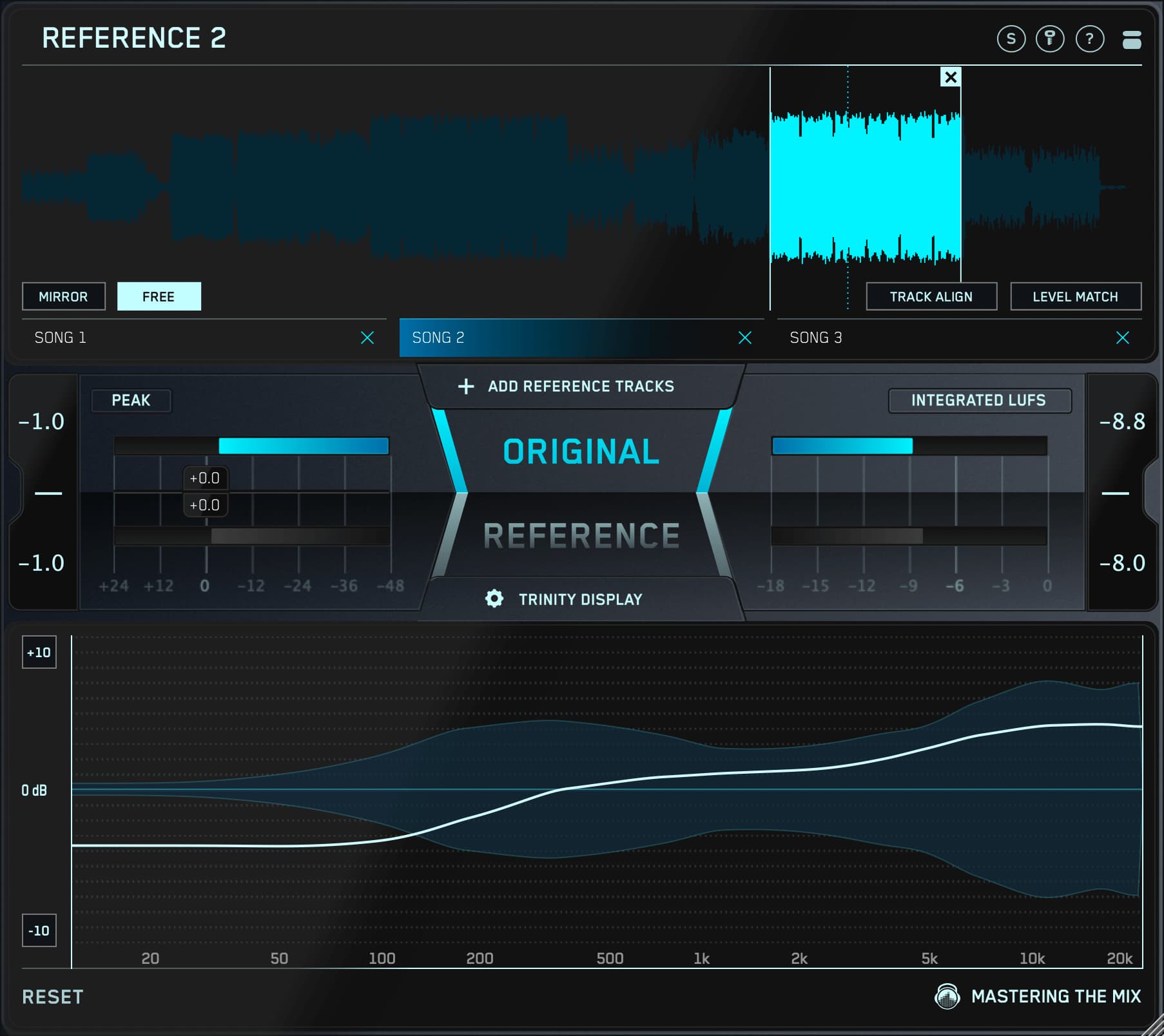

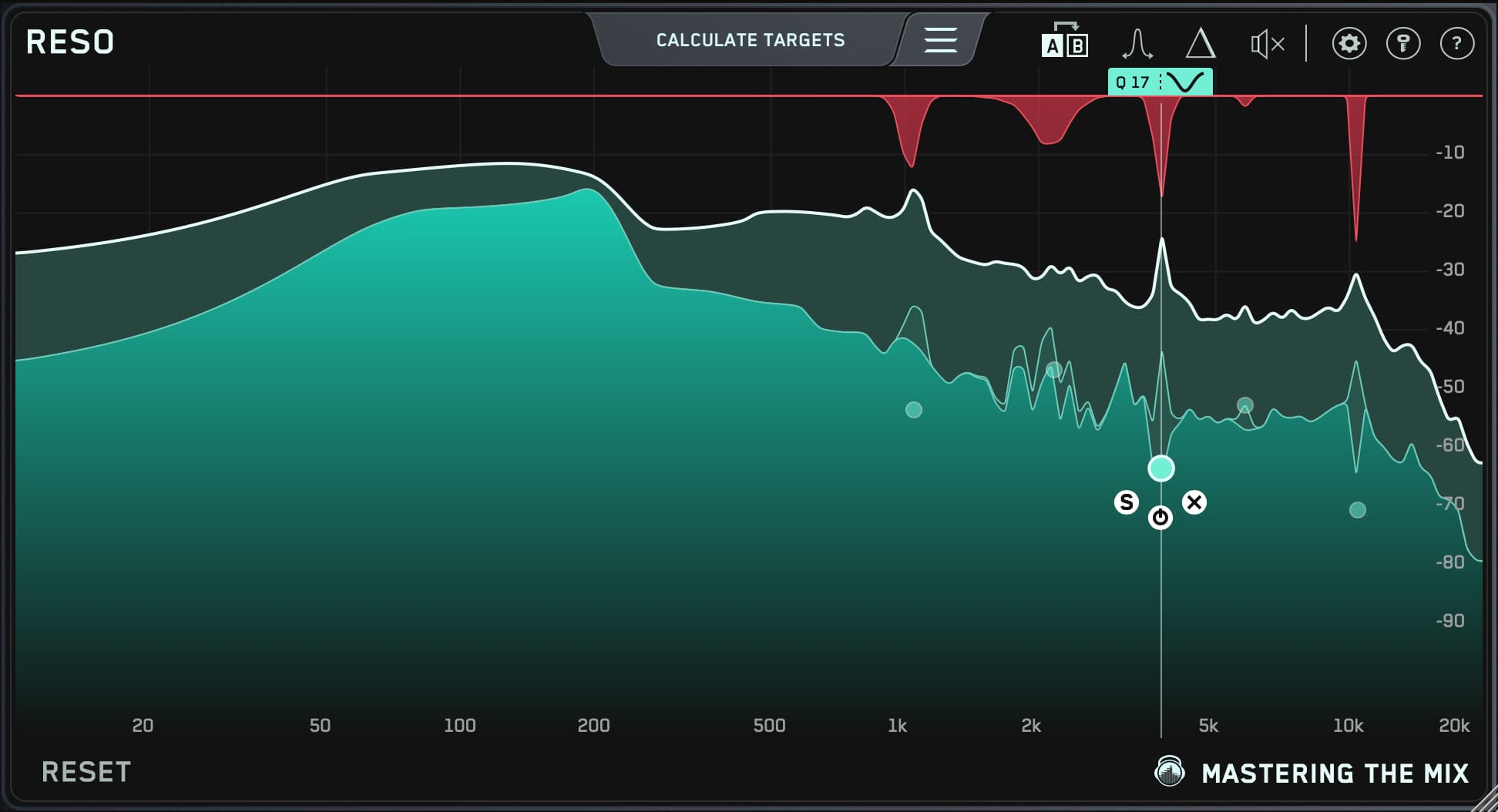

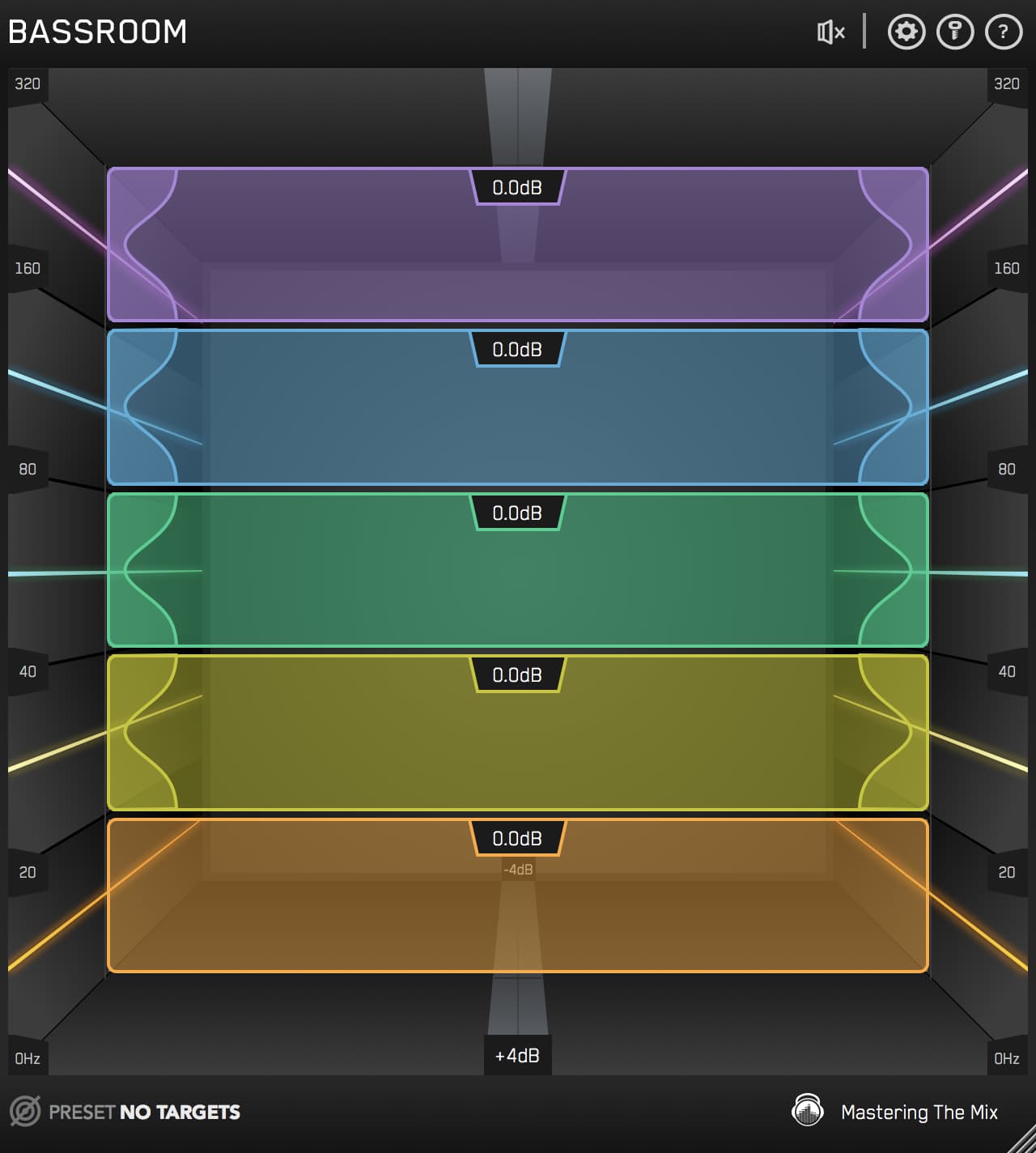

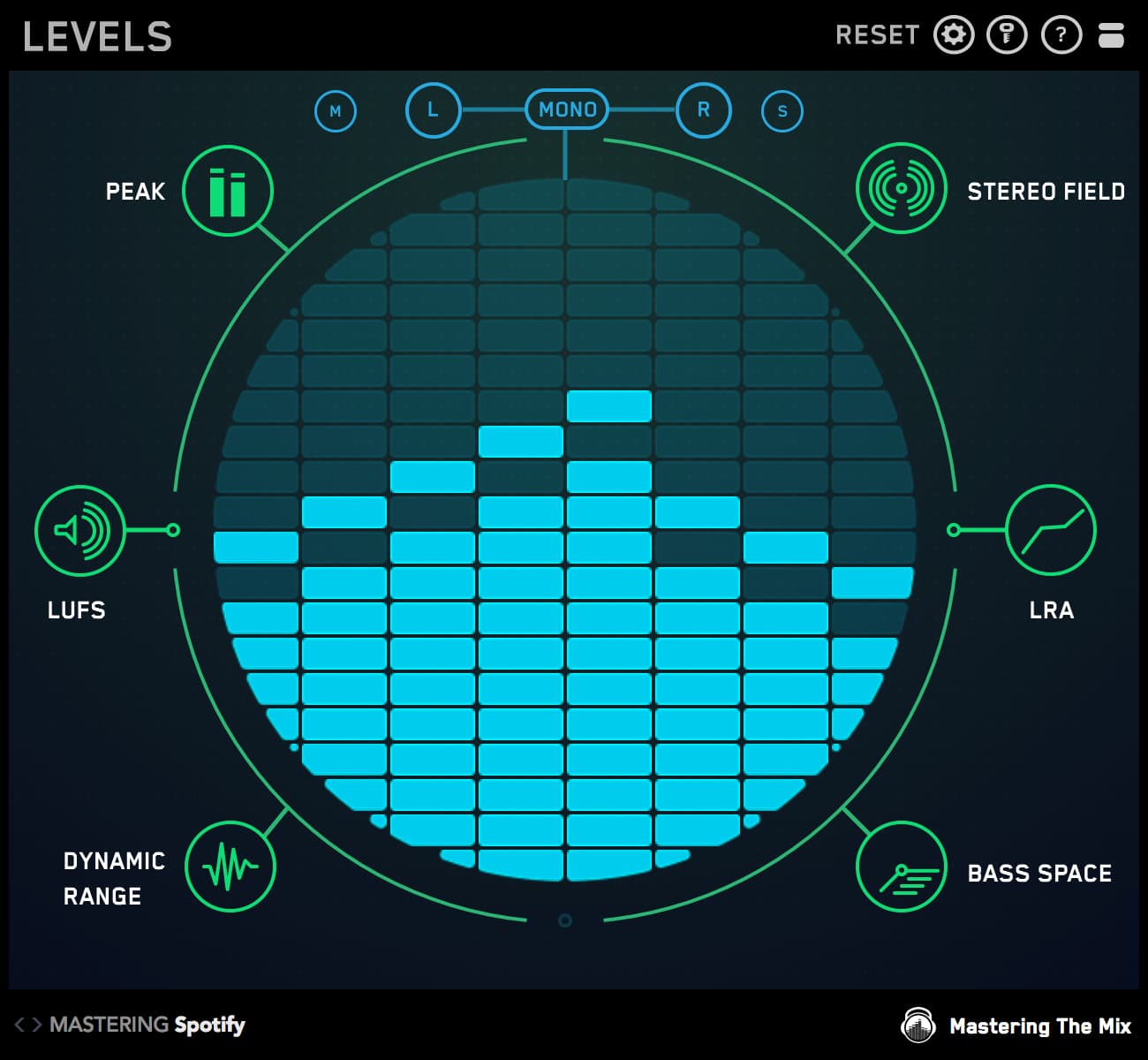

Our most basic tools are what will help us, but you can find joy in this, rather than despair: you need not own the fanciest plug-ins in the world to achieve depth. Your DAW’s plug-ins, with proper metering, will suffice (Most DAWs don’t usually come stocked with great metering, so we do recommend Mastering The Mix's LEVELS - a fantastic set of diagnostic tools).

Practice these principles in every mix, and you will see the results. So will your clients!

By Nick Messitte, Mastering the Mix Contributor