by Tommy Brett - Mastering The Mix Contributor

Due to its power to change and sculpt sound in countless different ways, Equalization is one of the most powerful tools in a mixer’s arsenal.

Whether you’re using it for broad, musical boosts to enhance the punch or excitement in a track, or narrow, surgical cuts to remove unpleasant build-ups and resonances, it’s just a must-have if you’re looking to produce professional-quality mixes and masters.

The Basics Of EQ

If you’re new to audio, you can basically think of an Equalizer as a set of volume faders/knobs which allow you to control the relative levels of specific tonal ranges within a sound.

While a typical volume fader/knob can make an entire instrument louder or quieter as a whole, an EQ essentially allows you to split that signal into multiple “Bands” (lows, mids, and highs, for example), and cut or boost each of these ranges independently from each other.

If you’ve ever used an affordable hardware sound-board/mixer, you’re most likely already familiar with the kind of simple “3-band” equalizer design. These will typically consist of low, mid and high bells/shelves at set frequencies for basic tone-shaping purposes.

In professional studio mixing, this concept is often taken a step further in the form of Parametric Equalizers, which allow for an almost infinite number of EQ bands, and superior customisation of parameters like frequency, gain, curve and Q (width/resonance).

Now that we have a better understanding of what EQ’s are, let’s take a look at how we can actually go about using them to make recordings sound better.

Mixing With Equalizers Getting Started

First off, I’ll start by saying that technically, there’s no such thing as “right” or “wrong” when it comes to equalization (or anything mixing-related for that matter).

Being that no two instruments, microphones or voices are identical, the “perfect” settings that work well for one sound may not work for another, and vice versa.

This being said, there are some universal “rules of thumb” that will produce decent results on pretty much anything. So, let’s take a look at a few of them and get you started on your equalization journey.

The General Rules of EQ

1. Broad, “Musical” Boosting

When you first listen to pretty much any “raw” audio recording, like a vocal captured with a microphone, or guitar plugged straight into an audio interface, chances are things are gonna sound fairly “dull” and “flat”.

While these “qualities” aren’t necessarily a problem as long as you’re listening to said source in solo (as they aren’t yet having to compete with anything else), the moment you place them in context of a full arrangement with bright cymbals, booming bass, and harsh distorted guitars, they’ll most likely just get completely lost in the mix.

The single most powerful EQ move you can apply to these kinds of raw recordings straight-off-the-bat to instantly take them most of the way from “boring and lifeless” to “exciting and professional”, is to give them a broad, generous (+5-10dB) upper-mid/treble EQ boost using either a shelving or bell band in the 5-10kHz range.

In the case of instruments that don’t play a primarily “low-end focused” role, like guitars, keys, horns, or vocals, I’d even go as far as saying that if you’re only able to apply 1 EQ move per instrument (for whatever reason), make it this one.

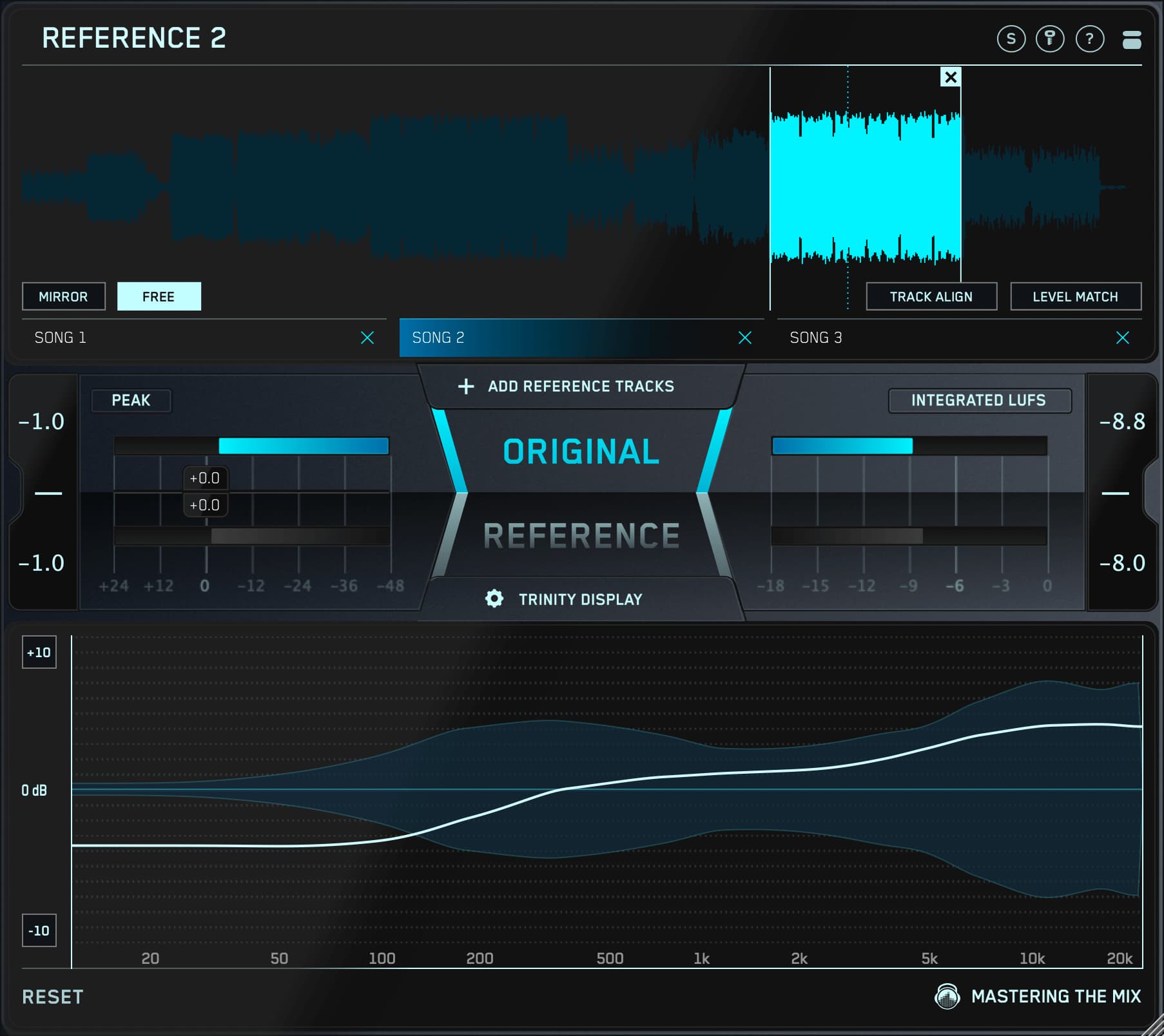

When boosting high-end, it’s important that you use the right tool for the job. A plugin like our mastering-grade MIXROOM equalizer plugin allows you to lift the treble of pretty much any source in an extremely clean & musical manner.

A high-band set at 5-8kHz upwards by +5 to 10dB is the perfect choice when you’re aiming for bright, present, clear sounding vocals, drums and guitars. Simply push it to where things are sounding great, and call it a day!

The same logic also applies at the opposite end of the frequency spectrum when dealing with low-end-focused instruments like kicks and bass guitars/synths. Depending on the genre you’re working in, often just applying a single, broad, strategic low-end (bass) boost at the right frequency is all it takes to make a big difference.

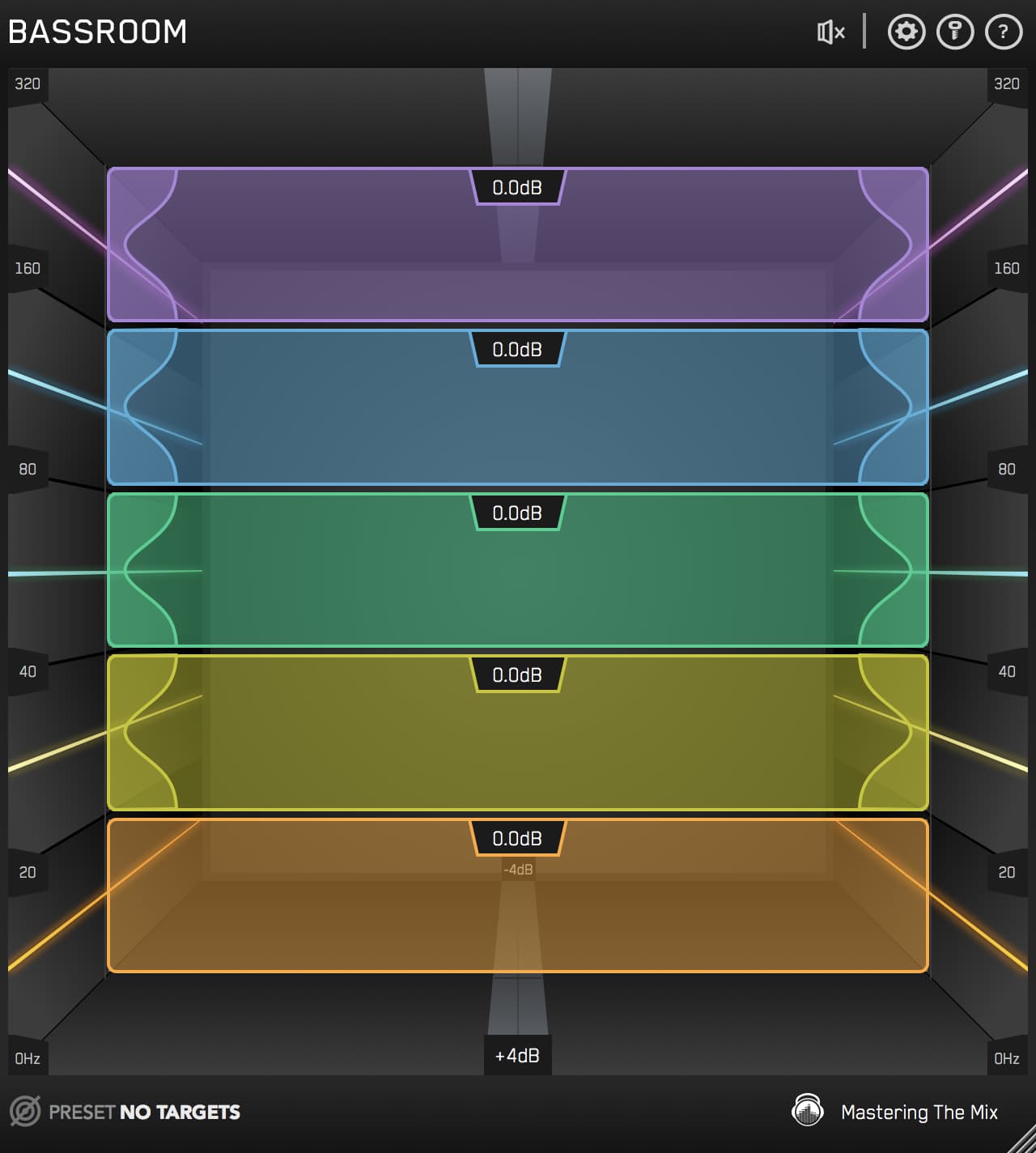

Similar to the MIXROOM example we’ve just looked at for the high-end, our BASSROOM equalizer is a fantastic choice for boosting clean, punchy, thick low-end into kicks, bass guitars or sub synths.

The 60-80Hz band is perfect for giving kick drums some nice chesty low-end “thump”, while the 80-160Hz band tends to sound great on bass guitar. Again, just simply lift them until things are sounding nice and fat!

Fun-Fact: While you may think world class mixers like Chris Lord-Alge (Green Day, Paramore), Andy Wallace (Linkin Park, Jeff Buckley) and Andrew Scheps (RHCP, Jay Z) are using a ton of complex, “secret” mixing tricks to achieve their punchy & exciting signature sounds, a lot of it actually just comes down to their bold usage of strategic low and high shelving on pretty much every instrument.

2. Broad “Sculpting” Cuts

There are two types of mixing engineers: the “subtractive” ones, and the “additive” ones. The thing is, believe it or not, both approaches can actually achieve the exact same results...

Don’t believe me? Check out the following video demonstration for some conclusive proof:

So, just in case you missed it: By boosting +10dB at 1kHz using a high shelf on one of our drum loop duplicates, and cutting -10dB at the same frequency with a low-shelf on the other, we’re actually applying the same exact same EQ curve to both channels, albeit, with a 10dB level difference between them.

With two signals volume matched, and the polarity for one of them reversed, the result of summing them together is total silence, aka, they’re canceling each other out entirely due to them being 100% identical. Science!

Now, the problem arises when beginner engineers come across generic mixing advice online along the lines of “When mixing kick drums, make a big, wide cut at 300-600Hz to remove the mud and boxiness, and then ALSO boost a ton of broad, significant highs and low-end”.

Thinking back to when I was an impressionable newcomer to audio nearly 15 years ago, I’d follow this kind of well-meaning, yet realistically somewhat unhelpful advice to the letter, and most of the time, just end up with super-bright and scooped sounding drums as a result.

You see, if you make a huge cut in the mid-range, AND boost a huge amount of highs and lows, you’re essentially just doing the same thing TWICE...

Long story short, the main point I’m really trying to get at here is: When EQ’ing, you want to quickly pinpoint the primary issues within a sound and resolve them in as few moves as possible to maintain listening objectivity and ensure natural-sounding results.

In the case of a vocal which sounds dull and muddy, for example, the quickest way of achieving this goal is to start by either applying a big, broad 5-10kHz shelving boost, OR a big, broad cut in the lows/low-mids.

For this purpose, I personally tend to prefer the additive route, as it’s easier to hear boosts than it is cuts, but either way, you want to be making your move fast, boldly and confidently.

After you’ve resolved the most “major” issue(s) in the recording, you can now go in on a more detailed level and resolve the remaining more “minor” issues using smaller, more-focused cuts.

The trick here is to only remove actual issues that are actually sticking out to you, and not just to go sweeping around for problems with a tight bell boost where there are none.

Anyway, there’s no rule as to how many bands of “sculpting” it should take to EQ an instrument. Depending on the quality of the particular recording you’re working on, it could take 0 bands, or it could take 10 - Basically, you just need to listen in context, and do whatever needs to be done to get things sounding clean and professional.

Again, when you first start EQing a track, before you dive straight in with dozens of bands of subtractive EQ in the mids, I’d definitely recommend trying out the “broad” high and low shelving method we mentioned earlier first, as it’s likely that a lot of those problems you’re hearing will become much less blatant anyway once the general tone has been corrected.

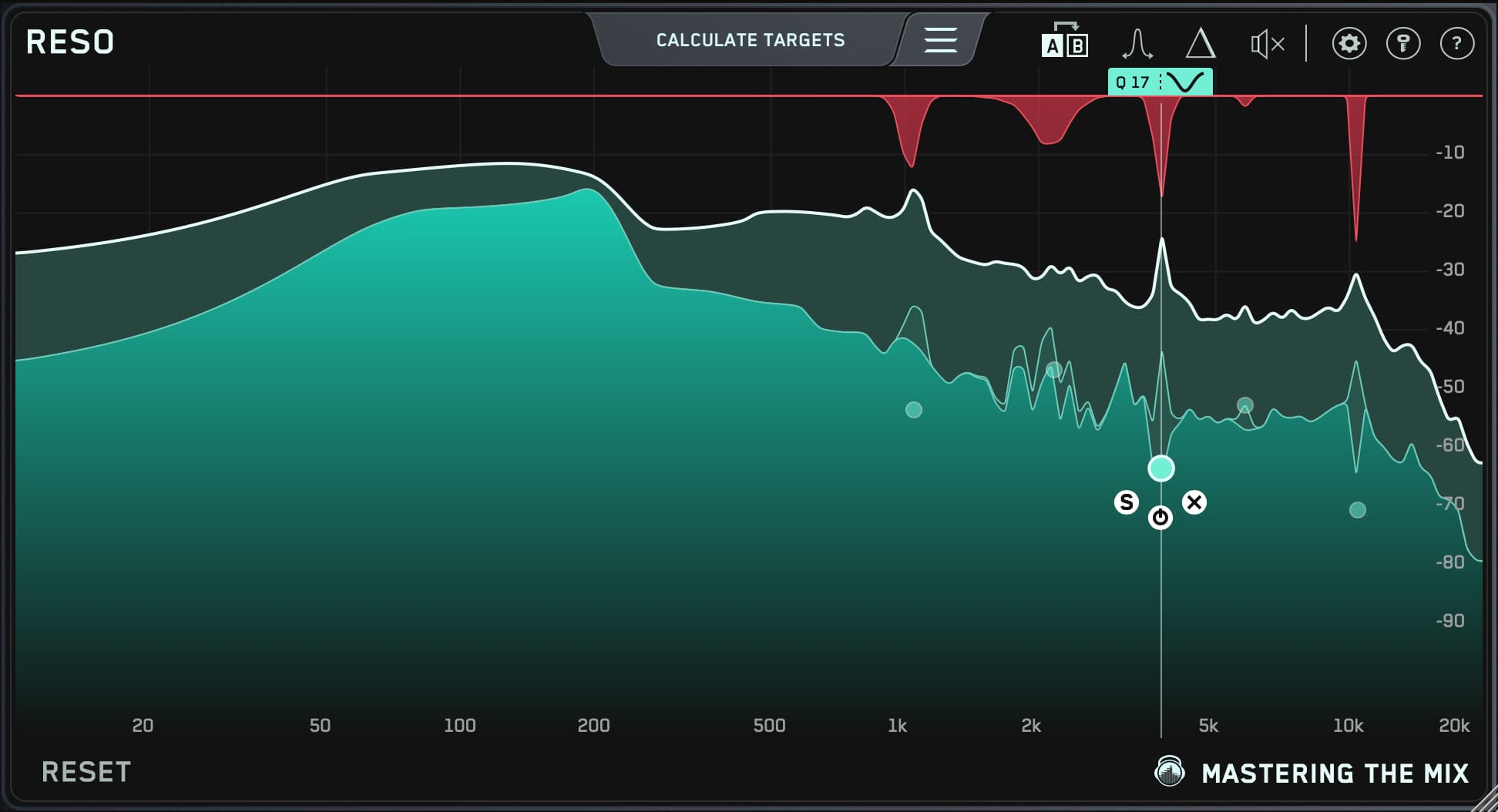

3. “Surgical” Resonance Removal

Now that your broad “tonal enhancement” and “corrective sculpting” EQ moves are complete, it’s time to get surgical, and hunt down any remaining resonances that are still sticking out as harsh or unpleasant.

Often a result of the gear used during tracking, or the space in which it took place, some recordings can have a few (or a lot of) these super-narrow “resonances”, or specific frequencies which just ring out disproportionately to everything else.

While minor resonances here and there aren’t usually a huge problem in the context of a full mix, in certain cases, they can be pretty painful to listen to...

As was the case with the “broad sculpting” we talked about in the previous section, you definitely don’t want to go looking for problems by sweeping around a super-tight bell band in solo at this stage, as everything will sound

bad when doing so. Only ever use this technique to pinpoint the exact location of problems you’re already aware of.

If you’re not yet at the point where you’re able to hear and pinpoint all of the unpleasant resonances in your tracks manually, you can always use our RESO Dynamic Resonance Suppressor plugin to do the job for you automatically in 3 steps.

Simply insert RESO on the problem track, click on the “Calculate Targets” tab at the top to automatically detect potential problem resonances, and finally, after the analysis is complete, click “Engage Targets” to engage the bands of dynamic resonance suppression which have been created. Easy as cake!

EQ is often viewed as a crazy-technical and scary process - A dark art which only the greatest “audio wizards” can master with 20 years of experimentation and experience...

As you’ll hopefully agree after reading this article, the reality is, it’s actually quite a simple and musical process if you’re thinking about it in the right way...

Just make sure you’re not overthinking or overdoing things, and are always trying to reach the end goal with the fewest number of strategic moves possible, all made in context of the surrounding musical “big picture”.

Practice, practice, and then practice some more, and eventually, you’ll get to the point where it’s all second nature!